Pumpkin Toadlet

Brachycephalus ephippium

The pumpkin toadlet is one of the smallest frogs in the world — only some 18 mm (0.7 in) long. Because of its minuscule size, the organs in its ears that are responsible for balance cease to work mid-jump. As such, it cartwheels rigidly through the air before making a clumsy, floppy landing.

On the Atlantic coast of southeastern Brazil,

petite pumpkin patches litter the floor.

They're found in the forest, on elevated hill,

like tiny, flame sprites from folklore.

They hide beneath leaves, and branches, and logs.

Their bodies; rich ochre and orange, hardly the size of a nail.

When the wet season comes, pouring forth rain, the pumpkins, they turn into frogs.

They croak and they shriek, they hop and they leap, and through the air, tumble and flail.

Tiny Toadlet

Poke and prod through the rainforest leaf litter and you might catch a peek at a bright orange critter doing its best to stay hidden. It might peek back at you with its large, entirely black eyes. Its limbs, short and gangly, barely hold up its burly body. It opens its toothless, gummy mouth to let out a shrill shriek. Congratulations, you've just met a pumpkin toadlet. But, if this toadlet resembles a pumpkin, it would have to be a very small pumpkin, for this is one of the smallest frog species in the world ¹ — with an average length of only 18 mm (0.7 in).

You can travel the entire world, but you'll only ever meet the pumpkin toadlet in one place; the neotropical rainforests along southeastern Brazil's Atlantic coast, typically at higher elevations between 700 and 1,200 metres (2,300 - 3,950 ft). If you visit during the dry season, you'll have to flip over leaves and peer under logs to find any sign of a pumpkin toadlet, for this is its season of hiding. The rainy season, from mid-October through March, is a completely different story. This coastal stretch of rainforest animates with countless tiny pumpkins, croaking and hopping about.

Jousting Jack-o'-lanterns

The rain awakens both lust and violence in the male toadlets. They cry out in shrill voices — advertising calls lasting between two and six minutes. In most frogs, these amorous screams serve to attract females, but the pumpkin toadlet's charms fall on deaf ears, quite literally. It was found that the toadlet's tiny ears aren't tuned to hear the frequencies of its own calls. This seems a glaring oversight; the calls don't serve their practical purpose of attracting mates, but can still attract predators. The likeliest explanation is that we're seeing evolution ‘in the making’ — as predators pick off the loudest males, the species may evolve towards muteness.

If a female happens to turn up — irrespective of the male's useless calls — the male toadlet will move his arms up and down over one eye and whip his head with his limbs in an enthusiastic sign of welcome. He then follows her very protectively — grasping onto her rear — as she looks for a spot to deposit her eggs; typically under some leaf litter or a log. She pops out about five yellow-white eggs, which the male dutifully fertilizes, and then she kicks them around, rolling them in dirt to camouflage them, before leaving forever.

A meeting between two males goes a bit differently. Few words can describe the ire male pumpkin toadlets feel for one another. There are no platonic friendships among the males; they are solitary and their sole interactions are in battle. A retelling of a pumpkin toadlet brawl reads much like a bar fight between two belligerent drunks.

Confrontations begin with high-pitched vocalisations, followed by a lot of posturing — moving their arms up and down in front of their eyes. If things escalate, they begin to kick one another, and one toadlet typically ends up mounting the other. The dispute is resolved when one toadlet calls it quits.

Females, on the other hand, just seem indifferent. They don't fight one another, but they don't particularly want to be around each other either. No battles, less stress — surrounded by hot-headed males, they remain unbothered. But what about other stressors? The rainforest is a competitive place. Every predator needs its prey, after all. Springtails ², for example, must watch out for the voracious, toothless jaws of the pumpkin toadlet. Larger, feathered beasts also hunt along the jungle floor, such as guans and tinamous. ³ Few predators, however, would be willing to make a meal of the pumpkin toadlet.

Poisonous Pumpkins

We make all kinds of delectable dishes from pumpkins; pies and porridge, soups and spiced lattes. The pumpkin toadlet, however, is not so delectable. Its alluring orange exterior hides a concoction of poisons; mostly within its skin, but also in its liver and ovaries. This frog brews up small amounts of tetrodotoxin — the same neurotoxin that makes fugu, or the Japanese pufferfish, such a risky meal — which, when ingested, can cause hallucinations. However, if you go and eat this toadlet hoping for a whimsical journey through a hallucinatory pumpkin patch, your fun will quickly be cut short by serious damage to your lungs, muscles, and nervous system, and potentially a death via cardiac arrest.

The pumpkin toadlet's internal arsenal of poisons is likely why it can be so vividly orange. Its neon skin can easily be spotted by any decently-sighted predator. But, at the same time, this bright colouration serves as a kind of biohazard symbol, which strongly disinclines predators from making the frog a meal — a strategy known as aposematism. ⁴

Graceless Gourds

The pumpkin toadlet's poison, perhaps, makes up for its complete and utter lack of grace and, some might say, competence. Frogs and toads are expected to do a couple of characteristically froggy things. Croaking for one — which the pumpkin toadlet can do, if a bit squeakily — and hopping. The pumpkin toadlet falls a bit short on this second requirement.

It's got the first part of hopping down pat; its limbs propel its body off the ground and into the air in a mighty leap. However, once in the air, it seems to just give up. Rather than folding its legs up to its body, like other frogs do to shoot straight through the air, the pumpkin toadlet goes completely ridged with all its limbs still extended; performing several airborne flips and cartwheels before flopping onto the ground, onto its belly or back.

Entertaining as this is, it can't be very beneficial to the toadlet. Why then, is it such a poor hopper? The answer appears to be its size. The size of an animal's organs corresponds with its overall body size — obviously, you physically couldn't fit a human-sized heart inside a tiny toadlet, and the reverse would be pretty ineffective at pumping blood around a giant body. But, some organs just seem to function poorly when scaled down.

One such organ is the vestibular system; structures within the ears of vertebrates that give us our sense of balance. When we move, fluid sloshes around within this structure, activating sensory hairs that send signals to the brain, informing it of our head's orientation in space. ⁵ The fluid-conducting tubes within the frog's inner ears are extremely small and narrow, making it difficult for the fluid to flow freely. When the pumpkin toadlet leaps, it accelerates quickly, but the fluid can't keep up and the toadlet essentially loses all sense of spatial awareness while in the air. And so, instead of a controlled leap, it performs a hop, tumble, and flop.

¹ As far as we know, the world's smallest frog species is a brown speck of an amphibian known aptly as the Brazilian flea toad — a close relative (in the same genus, Brachycephalus) as the pumpkin toadlet. The previous titleholder for the tiniest toadlet was the New Guinea Amau frog — hailing from across the Pacific and measuring 7.7 millimetres (0.3 in) long. However, the more recently discovered flea toad from Brazil surpasses it in smallness; with males (the smaller sex) measuring 7.1 millimetres (0.28 in) on average. This difference of 0.6 mm, while shifting the leaderboard, is a bit overscrupulous. Both species, after all, don't even reach the halfway point on a U.S. dime — a smaller frog is hard to imagine, let alone find. And not only are these the world’s smallest frogs, they’re also smaller than any other known vertebrate.

² Springtails are tiny bugs (not technically classified as insects) with rounded soft bodies, and are typically found in places with high moisture, munching on decaying roots and fungi. They don't harm humans, don't damage food or clothes, and rarely injure plants. They can be bothersome if you find them springing about in your home — getting several inches of air using specialised forked structures under their abdomens — but they won't hurt anyone. Nonetheless, they’re still considered pests by their presence alone.

³ The main threats to the pumpkin toadlet are ground foraging birds. Examples include the rusty-margined guan — a dark and handsome pheasant-like bird with a red wattle — and the solitary tinamou — as its name suggests, it is quite secretive; it's also not much to look at, being drab, dumpy, and almost tailless.

⁴ Advertising yourself to predators is a bold survival strategy, but if you can back up all the glitz, it's a strategy that works.

You've probably encountered aposematic warning signals most frequently in animals like wasps or bees — their bright yellow-on-black bodies warn you not to touch (or eat), and if you don't heed that warning the first time, you'll eventually learn to after some painful trial and error. Another possibly familiar example is the six-spot burnet moth, which could have been quite stealthy, with its dark wings and body, but instead "chose" to be decorated with six vivid red spots (hence the name); advertising its ability to produce hydrogen cyanide when attacked. Even butterflies like the monarch, beautiful as they are, are often filled with toxins from the plants they eat, potentially causing harm to predators, and ultimately dissuading them from taking a bite.

Some of the most colourful animals on the planet are so unabashedly vibrant for exactly this purpose. Famous examples include the extremely poisonous poison dart frogs, the extremely venomous coral snakes, and even the extremely stinky skunks (the latter, although not colourful, are very conspicuous and recognizable with their black-and-white patterning). Other animals add nasty-looking appendages in addition to their colours — no one in their right mind would want to touch, much less eat, a crown-of-thorns sea star or a gulf fritillary caterpillar. And, while the most obvious examples of aposematism are visual, it can take any form that effectively signals danger, such as the rattling hiss of a rattlesnake's tail.

Aposematism works so well, in fact, that it's led to the evolution of animals that themselves aren't dangerous but mimic the appearances of those that are — in other words, these mimics are all bark and no bite, or, in more technical terms, this is known as Batesian mimicry. Examples include bee mimics, such as hoverflies and drone flies, that have no stinging defences of their own, non-venomous milk snakes that mimic mildly venomous false coral snakes, and many species of non-toxic butterflies that benefit from borrowing the looks of toxic neighbours.

⁵ When you spin yourself in a circle for a while, the fluid in your ears begins to move quickly along with you, and when you stop spinning, the fluid keeps moving; signalling to your brain that you're now spinning in the opposite direction when you're actually standing still — causing you to feel dizzy.

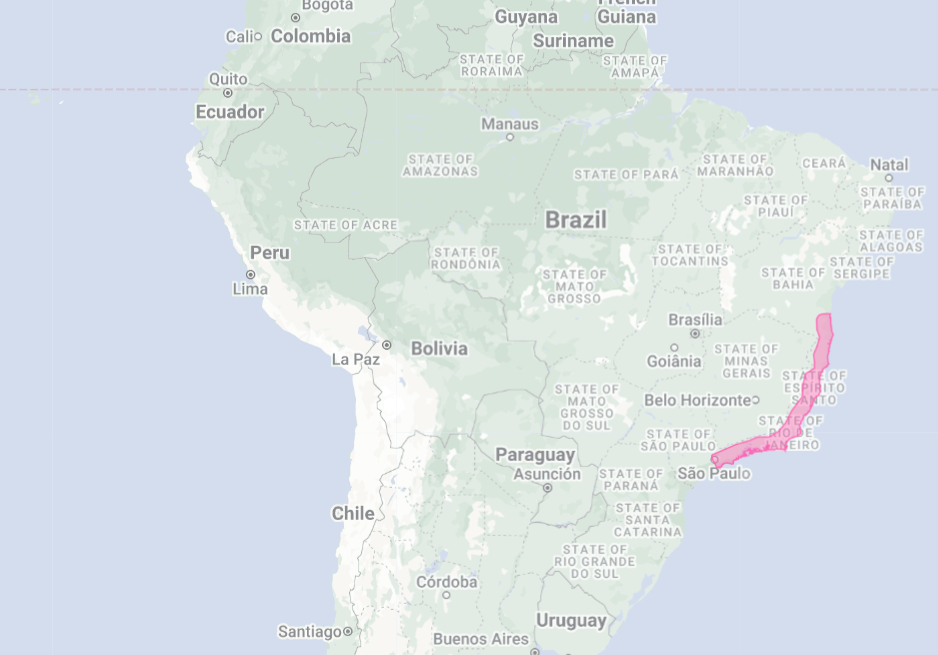

Where Does It Live?

⛰️ Montane Atlantic coastal forest.

📍 The Atlantic coast of southeastern Brazil; in Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, southeastern São Paulo and southeastern Minas Gerais.

‘Least Concern’ as of 09 April, 2021.

-

Size // Tiny

Length // 18 mm (0.7 in) on average

Weight // N/A

-

Activity: Diurnal ☀️

Lifestyle: Solitary 👤

Lifespan: N/A

Diet: Carnivore (Insectivore)

Favorite Food: Springtails, and insect larvae and mites 🐜

-

Class: Amphibia

Order: Anura

Family: Brachycephalidae

Genus: Brachycephalus

Species: B. ephippium

-

The pumpkin toadlet has a squat physique, with short limbs, making it an awkward, bumbling walker — it's just not great at locomotion in general.

Its front limbs have four digits (but only three are functional) while its hind limbs have five (but only four are functional).

In vertebrates, including us, the structures responsible for balance (called the vestibular system) are found inside our inner ears. When we move, fluid sloshes around within this structure, activating sensory hairs that send signals to the brain, informing it of our head's orientation in space.

However, the fluid-conducting tubes within this frog's inner ears are very narrow, making it difficult for the fluid to flow freely. When the pumpkin toadlet leaps, it accelerates quickly, but the fluid can't keep up and the toadlet essentially loses all sense of spatial awareness while in the air, causing it to seize up and tumble.

Pumpkin toadlets can only be found in montane rainforests along the Atlantic coast of southeastern Brazil.

During the dry season, they hide out beneath leaf litter and logs. But when the rainy season arrives, the males become belligerent and lustful.

To advertise himself, a male toadlet emits loud, buzzing croaks that can last from two to six minutes.However, this toadlet's ears aren't tuned to hear the frequencies of its own calls — females cannot hear the flirting males.

If one male enters another's territory, they initiate a drunken brawl. First, they screech shrilly at one another, then they posture — moving their arms up and down in front of their eyes — then they finally fight. They kick with their hind legs and one combatant usually ends up mounting the other.

A male enthusiastically welcomes a female into his territory by moving his arms over one eye and whipping his own head with his limbs.

Once a male has a female's favour, he clings to her rear and follows her around until she finds a place to lay her eggs — which he will fertilise.

After laying around five eggs, the female kicks them about in the dirt to camouflage them and then leaves.

The young lack a larval stage; hatching into miniature toadlets with vestigial tails that they eventually outgrow.

The pumpkin toadlet can produce tetrodotoxin in its skin, liver and ovaries; a neurotoxin that can cause hallucinations, as well as organ damage, and possibly cardiac arrest.

This toadlet forages under leaf litter for tiny springtails and insects, as well as their larvae. The toad lacks teeth, instead using its strong jaw and dermal bones to munch on its prey.

The pumpkin toadlet belongs to the genus Brachycephalus. This genus (known as flea toads) contains the smallest currently known frog species, and vertebrate in general, the Brazilian flea toad — an average mature male measures only 7.1 millimetres (0.28 in).

-

Evidence of auditory insensitivity to vocalization frequencies in two frogs by Sandra Goutte, et al.

BBC - Brazilian flea toad

Smithsonian Magazine - Brazilian flea toad

Science - New Guinea Amau frog

Hippocampus: University of Newcastle - why we feel dizzy from spinning

University of Minnesota Extension - springtails

The Wildlife Trusts - siz-spot burnet moth

American Museum of Natural History - aposematism

University of California Berkeley - aposematism

University of Florida - gulf fritillary

BugGuide - Batesian mimicry

North Dakota: Game and Fish - Batesian vs. mullerian Mimicry

-

Cover (Carlos Otávio Gussoni / iNaturalist)

Text #01 (André Zambolli / iNaturalist)

Text #02 (Maria Ogrzewalska / Flickr)

Text #03 (Bernardo Rodrigues Ferraz / iNaturalist)

Text #04 (Richard Essner / Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, Mongabay)

Text #05 (Luciano Bernardes / iNaturalist)

Text #06 (Renato Gaiga / Smithsonian Magazine)

Text #08 (Roger Williams Park Zoo, jon hanson / Wikimedia Commons, Stan Tekiela / Discovery, and Aaron_G / Project Noah)

Text #09 (Andreas Trepte / Wikimedia Commons, The Suffolk Pest Control Company, Ryan M. Bolton / Shutterstock.com, Smithsonian's National Zoo, and Henry Walter Bates / Wikimedia Commons)

Slide #01 (Norton Santos / iNaturalist)

Slide #02 (Renan Castro / iNaturalist)

Slide #03 (Adam Carvalho / iNaturalist)